Neither/Nor Records

Sean Ali interviewed by Carlo Costa in March 2021 for the release of A Blink in the Sun (n/n 016)

Sean Ali: What interests me most about using words and music together is the overlap of the two and the deep, ancient, connection they share. This overlap is most clearly evident in the genre of poetry, one of the few categories of literature where the sound of the language demands as much of priority (sometimes more) as does the content. Typically, the impulse to take words into music consists of setting the words to melodies. What I am interested in doing is allowing the words to express their own musicality without melody. Even before I conceived of the bass parts for this album, I wrote all of the text to be heard. I thought of my audience as listeners instead of readers. Conversely, I've always been drawn to the narrative quality of instrumental music. The introduction of themes, the building of said themes towards a climax, the use of tension, thematic repetition and variation, are all essential elements that music shares with storytelling. It is impossible for me to pinpoint exactly when or how this interest started. Rather than a singular origin point, this combination of spoken word and instrumental music evolved slowly over decades as two passions of mine running in tandem with each other that converged over years of writing, composing, and performing.

CC: The work of Samuel Beckett seems to be a strong theme in this album or even a point of departure in some respects. Was this something you planned on or did his influence just reveal itself during the process? Can you speak about your relationship with Beckett's work?

SA: The track "Something Wrong Here" is a reference to How It Is (my favorite novel by Samuel Beckett and probably my favorite work of literature in general), which uses the phrase "something wrong there" in repetitive variations through text. Otherwise, none of it was consciously planned, but I am probably always subconsciously conjuring Samuel Beckett's spirit whenever I engage in any creative endeavor. There is so much that can be said about what Beckett was doing narratively, thematically, and aesthetically, that I would require a lengthy essay to discuss it, and these surely are already in abundance. But just to speak about my personal relationship with Beckett's work, what is perhaps the single most important thing for me is his transcendence of language into pure musicality. It would be a gross understatement to just describe his language as poetic. His language is music. I don't believe that anybody who reads his work silently will fully comprehend what he is doing. It must be read out loud and listened to. His words need to pass through your ear just as much, if not more so, than the printed word needs pass through your eye. Also, no matter how abstract Beckett's work gets, he has a predilection for concrete imagery and simple repetitive phrasing, and this has an appeal to me as a bassist, no matter how far away I've gone from traditional bass playing. So, these are some of the big, general ways that Beckett has influenced me overall. Regarding this album particularly, which, as a solo album, I wanted to explore my inner self, to reveal and obscure. Beckett's fractured, unreliable first-person narrators provide something of a pathway for this.

CC: Can you talk about the process of putting this album together? From writing the text and composing the bass parts, to recording and editing everything together. To what extent and in what ways did you make use of improvisation in the process?

SA: This album is the result of a slow and simmering process that developed over several stages. For several years now, I had been integrating text recitation into my solo bass performances, sometimes improvisationally and sometimes compositionally. However, I didn't really touch on this much in My Tongue Crumbles After, my first solo release, and it now seemed to be the time to explore it. Initially, I was only thinking pragmatically about recording the music. I originally envisioned recording something akin to how I performed with text and bass live: simultaneous text recitation while playing solo bass. I assumed that when it came time to mix the album, it would be helpful if the text was recorded on separate tracks, so I planned to record just the text first and then the bass parts later. Once I began this process, however, I really started to run with it. Instead of reading the text straight through, I experimented with repeating parts again and again. I experimented with whispering voices and speaking voices. Then I took that approach to the bass parts, layering bass tracks on top of each other in ways that either complimented or contrasted to what was happening with the voices. Although very simple, it was a major personal breakthrough to approach the album in this way. Pop musicians are very used to approaching recordings this way, as overdubbing and editing are salient features of recorded pop music. In the small and rarified world of improvised acoustic music, however, I feel there is an unspoken value placed on "purity of performance" in recordings that tacitly states that you shouldn't record what you can't play live. I think this comes largely from the fact that albums of improvised music are considered documents of what happens at live concerts. The subtext of this though is that the albums of improvised music are never as good as the live performances. That feeling, however, leaves me feeling nihilistic. What is the point of recording something that is bound to be a step down from the live experience? Recorded music so often falls short of the live music experience precisely because it is attempting to capture the uncapturable. So, I dispensed with that whole documentary method and decided to approach the album in such a way that the recorded experience was worthwhile on its own, even if that means that I will never be able to perform this music live. In other words, I was attempting to make a record that exploited its "recordedness" in the same way that a concert exploits its "liveness." At least, that's what I hope is the result, but the listener will be the final judge!

SA: Each track has a slightly different approach regarding the integration of voice and bass parts, but in general I kept my sights focused on the overall mood and atmosphere that I was trying to create while a lot of the particulars unfolded during the recording and editing process. The bulk of the text is thematically and emotionally connected, which gave me the freedom to play around with the bass parts. With the exception of "And Danced" and "Dialogue," I recorded most of the bass parts without a specific text referent. Rather, I recorded several different bass parts and then experimented with how each text piece sounded with them. This all sounds a bit like haphazard trial-and-error when I describe it this way, but my intuition for the sound of bass and voice had been in a process of refinement from several years of performing with text. I think that without having developed an ear for this particular sound, A Blink in the Sun wouldn't have amounted to anything more than a messy hodgepodge of basses and voices. Regarding post-production, the album virtually took its shape through editing. As I mentioned earlier, I took a no holds barred approach to post-production: adding subtracting, repeating, panning, etc. The raw recorded material sounds very different (perhaps even unrecognizably so) than the finished album you're hearing today. If I had to draw an analogy, I might liken the process to sculpture, a process which can be additive, subtractive, or assembly-based. What I recorded in the studio was like my raw material (my stone, clay, or wood, if you will), and editing was the shaping, carving, and assembling.

CC: In a recent email exchange we had regarding other matters you mentioned (I'm paraphrasing) that although these times have been challenging you’ve experienced a powerful new depth in music. Would you care to talk about it a little? I was quite taken by your words. They reminded me of how this moment is a good opportunity for us musicians to take a different look at our own practice, to get a bit closer to the core of what we do.

SA: The coronavirus pandemic both caused new problems and exacerbated existing ones. Like nearly all other performing artists, opportunities to perform and collaborate came to a total halt for a while. It forced me to look squarely at a question: why do I make music and is it worth it? I think all musicians reflect on this question throughout their lives, but the pandemic changed the dynamic by making the question one that confronted you instead of one you merely pondered. As an improviser, the live performance is essential to the experience of the music we make, so losing opportunities to perform posed a serious existential threat to the way I've come to understand myself as an artist. As difficult as the time as been (and I in no way wish to minimize or trivialize the very real suffering of others), there has at least been opportunities to look deeply inward and connect to the music you play without the distraction of superficial and/or practical things (networking for gigs, planning for tours, applying for grants and residencies, etc). There is only you and the music and the only choice is do you want to embrace it or walk away from it. This rediscovery/reaffirmation that the reason you make music is higher than all the mundane things we do in order to make said music is that "new depth" that I mentioned to you, and it is this feeling that has been a guiding force in creating A Blink in the Sun. I hope listeners are able to take this journey of rediscovery with me when they hear the album.

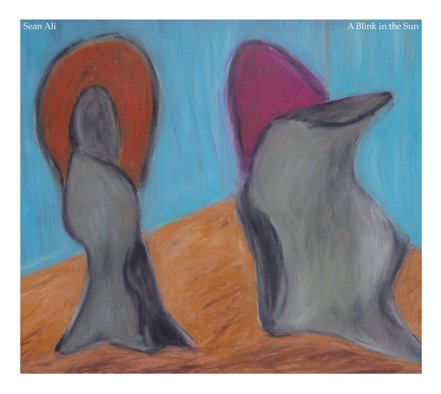

Photo credits and information:

The album cover is a painting by Sean Ali.

The photographs were taken by Carlo Costa in Forest Park, Queens on January 10, 2021.